An interview by Bart Sedgebear

Manchester Girl Came Long Way

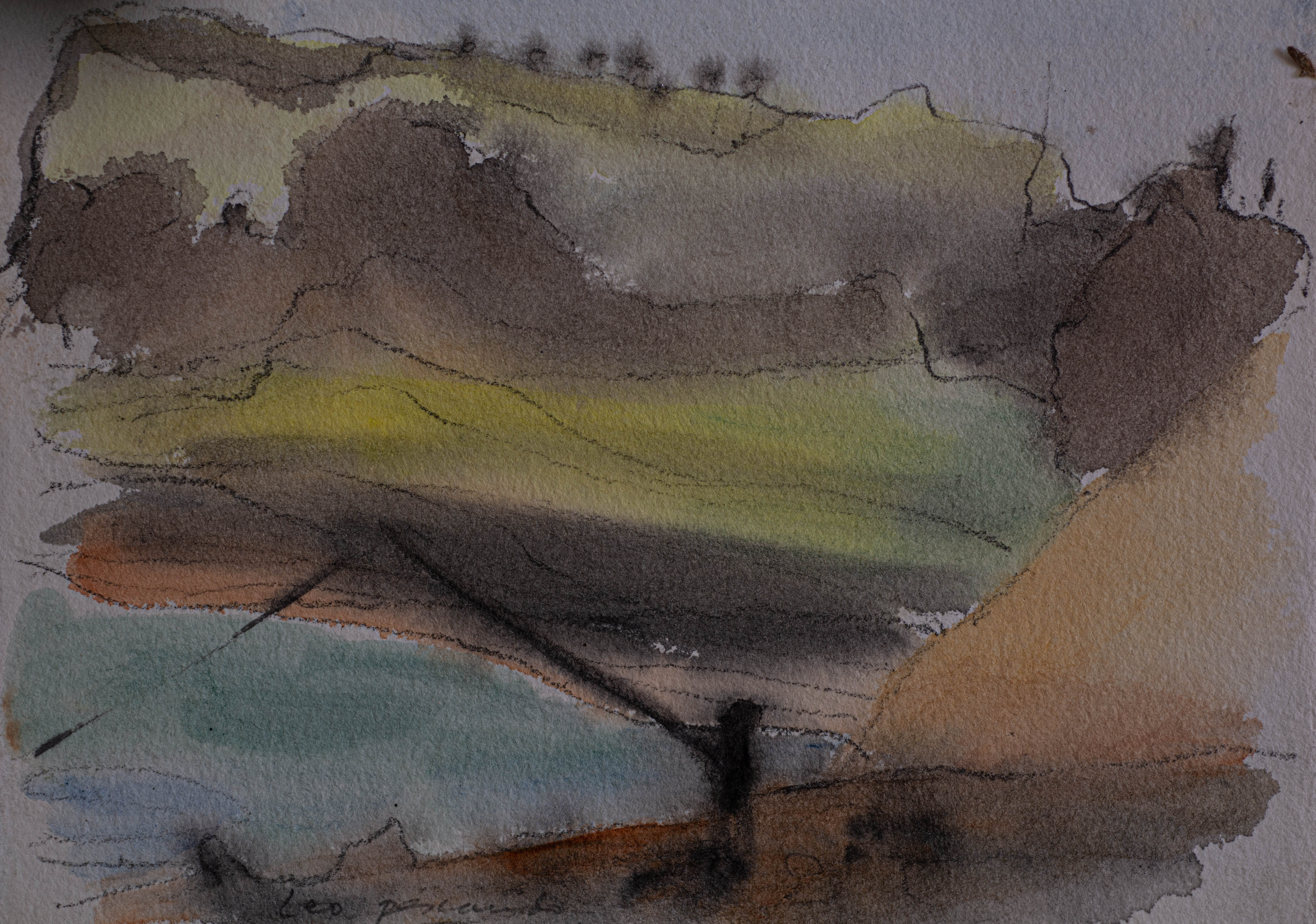

Maureen is from Manchester, U.K. In her last incarnation there she was a suburban housewife with two small children. That was in 1964 and she was feeling restless again. She had always been restless, at school, in church, in her job as a secretary earning coolie wages in the Manchester textile sector. This time it was bigger. She wanted out of suburbia, out of Little England. She had experienced only two weeks of sunshine in the previous year and yearned to feel the sun. She had painted her children’s bedroom walls with a bullfighter theme. Painting made her happy. She had attended a few night classes with a professor from the Stockport College of Art. “I needed to know how to stretch a canvas,” she says. After a half-dozen lessons the art professor said to her, “You don’t need to come any more. Just go home and draw everything.” She sold her first couple of portraits and thought the life of the artist would be easy.

One day, when her husband arrived home from work as a sales rep, she said to him, “Let’s move to Spain.” They had been on holiday a couple of times on the Costa Brava on Spain’s northern Mediterranean coast and enjoyed it.

In July 1964 she stepped off a plane at the Málaga airport, a thousand kilometers south of the Costa Brava. She was shepherding her two children and struggling with the carry-on luggage. Her husband was waiting there to drive them to their new home, a cobblestone, Roman-tiled fishing village 50 kilometers up the coast. As she stepped out the door of the plane she was buffeted by a wave of heat like nothing she had ever experienced before. She wondered if she had done the right thing.

Time Flies

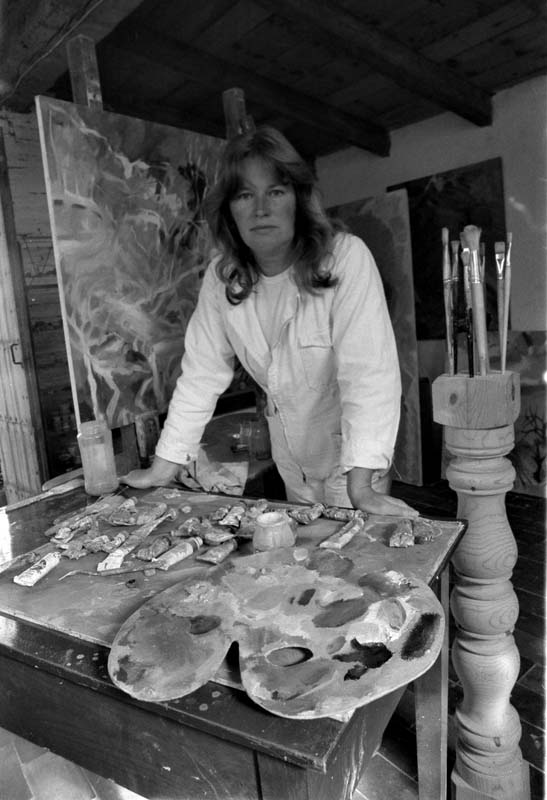

Flash forward a half century. She’s sitting midst easels and etching presses, stacks of canvases and exotic papers, worriedly anticipating the return of the wren that built his nest outside her studio window last week–and looking back over a life that took her by surprise.

Q: What happened?

A: We sold our house in England and pooled the money with another English couple to build a restaurant/bar and 12 apartments on a bluff over a Mediterranean beach in southern Spain. We ran the business working alternate weeks for a few years, the wives cooking and the husbands doing the shopping and tending the bar.

A couple of years in I rented the whole top floor of an old house overlooking a big vegetable patch and made it into a wonderful studio. The woman who owned the house was called Conchita Bueno and she was truly buena. I would paint there during the off weeks and any other time I could steal. Sometime during the fourth year, with the business taking off and me selling some paintings, I got restless again. We didn’t speak hardly any Spanish and we had never really integrated with the villagers. What’s more, the town was turning into a tourist trap for wayward Brits and Northern Europeans who formed English-speaking cliques and whose idea of adventure was to go to a “native” bar. It wasn’t an ideal place to raise children. I felt that I needed to get out of there. But how? I badly needed some serendipity.

It came along in the form of an American lad who wore cut-off jeans in mid-winter and always carried a couple of cameras. He moved into the ugly new block of flats opposite our restaurant and began coming over for breakfast, and we had time for long chats. It turned out he was writing articles for American newspapers and was determined to stay in Europe. He liked fried bread, had never heard of it. One morning he and I made mayonnaise together in the kitchen, him pouring the oil slowly into the bowl and me whipping it into the eggs with a wire whisk. Shortly afterwards we coincided at a party of those boring expats and spent the whole night in a corner reading aloud to each other from a book of Yeats’ poems. We read Beggar to Beggar Cried. That did it.

Q: What happened then?

A. Two weeks later I was back on the plane with my kids, headed to my parents’ house in Manchester. I was there for six months working in my brother’s flower shop while my soon-to-be second husband searched for a “real” Spanish village well off the Mediterranean coast, found one, rented a house there, and helped the owner install a bathroom. We’ve lived in that village ever since. It hasn’t changed much as it’s in a steepish valley that doesn’t have much room for “development.” Here we raised my two kids and one of our own.

Becoming a Printmaker

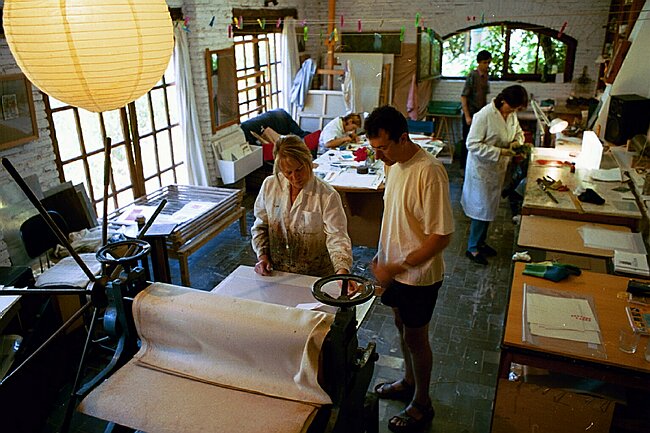

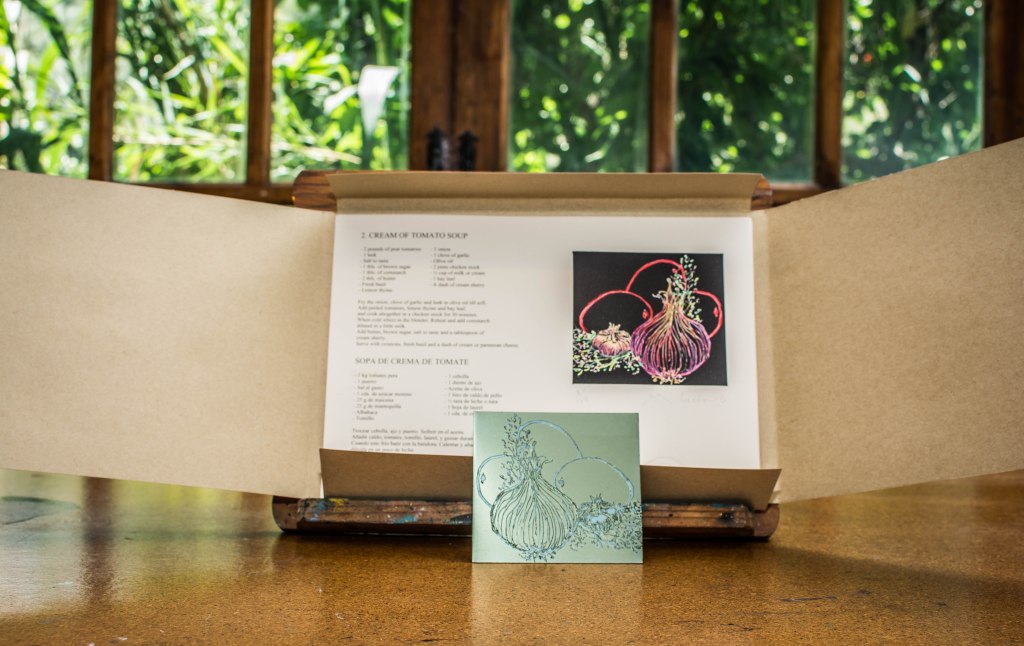

Eventually we bought an old house and fixed it up. As we had no money left nor collateral, the village mayor co-signed a loan for us to do the renovation. That is how our pueblo has treated us. Some years later we built the studio and converted the goat shed into an office for Mike and have happily lived and worked here ever since. Much later we built a cabin to accommodate the print artists who came from all over the world to attend my printmaking workshops. Workshops are what you do when a disastrous world economic crisis slows your flow of art sales to a drip. Even in this I was lucky. My husband was a freelance journalist and photographer who had worked in PR in the US, so it didn’t take him long to adapt to being an artist’s online publicist. Try googleing “printmaking courses in Spain” and see the first results.

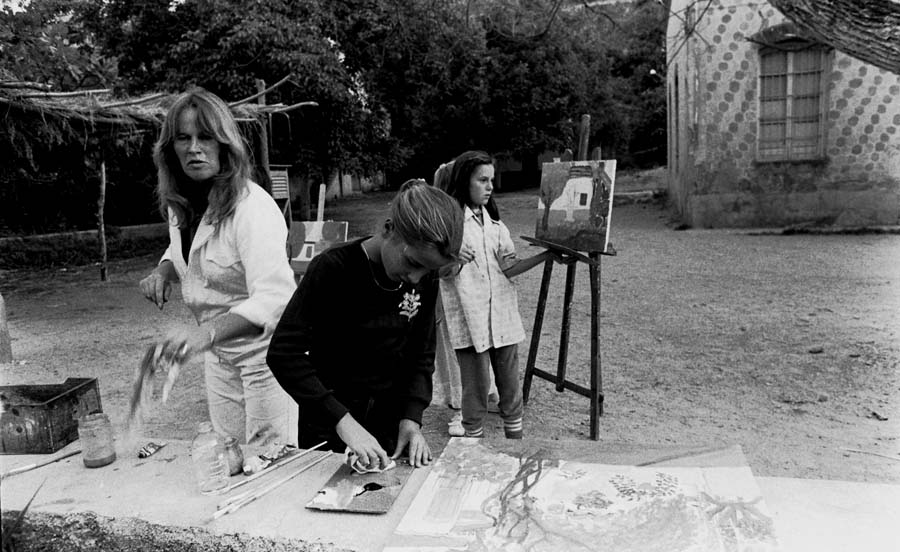

This was the etching studio of the Rodríguez-Acosta Foundation in 1979-80

Q: How did you become a printmaker?

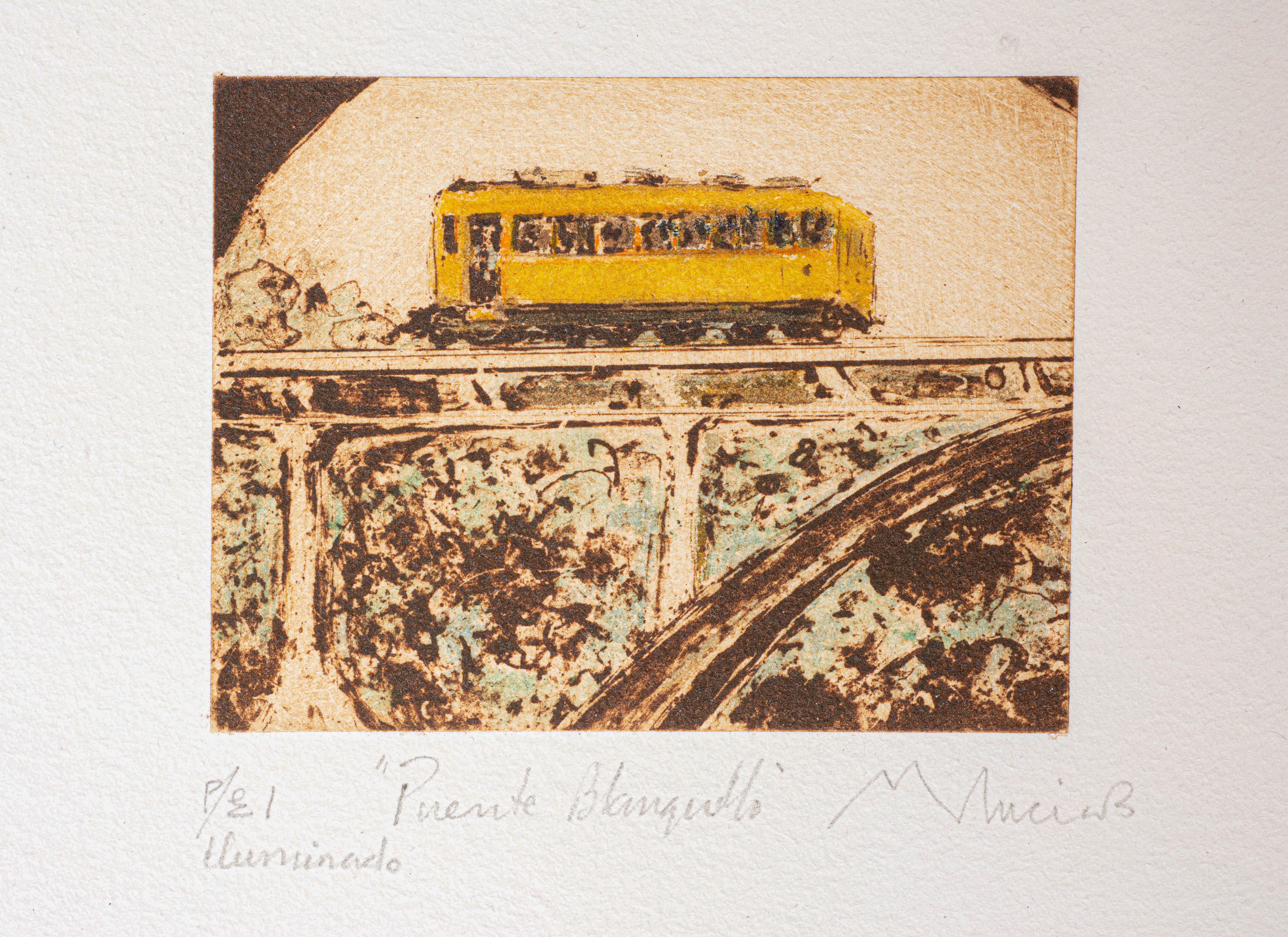

A: More serendipity. Louise Waugh, a wonderful English watercolorist friend, stopped by the studio one day with some beautiful etching proofs. I was astounded. How did she do that? She said she had been accepted to study in the etching studio of the Fundación Rodríguez-Acosta in Granada. “You just take a portfolio of your work and leave it with them, and then go back after a week to see if you’ve been accepted.” I did. I was. A whole new world opened up for me. I worked there for two-and-a-half years, under the direction of the magical printmaking maestro, José García Lomas, “Pepe Lomas,” who had been exquisitely formed in Barcelona and Paris. Pepe liked his students to be earnest and I was certainly that, so he spared no effort to see to it that I mastered his traditional techniques. It’s a good thing I did. Everything starts there.

The Creative Life

Q: Let’s talk about the creative life. How do you see it looking back?

A: And forward. That’s something I need to clear up. A writer friend of ours recently turned 40 and expressed concern about being “past her prime.” What nonsense. You’re never past your prime until you stop struggling. I made my first print when I was 37. Consider Georgia O’Keeffe, nearing 98, virtually blind, and still painting.

As for “the creative life,” Mike and I have discussed it a lot. We agree that authentic creativity goes beyond putting paint on canvas or ink on plates. For us an artist’s first mission is to take responsibility for crafting a creative life. That can mean different things for different artists but the essential part is about making a vital and artistic ecosystem for yourself, tailor made for your own needs, tastes, challenges and aspirations. And don’t fail to leave some space for serendipity.

Don’t worry what other people think of your lifeplan. It’s for you, not for them. Do you want to raise chihuahuas or learn Mandarin. You can do that, and more. When I was headed back to Spain in 1969 to start a new life my two brothers, both successful businessmen, expressed their grave concern for me. They thought I was crazy. Forty-some years later they came down individually for visits, and both confided to me, “I wish I had done what you did.”

Q: Do you have any advice for young artists who are starting out, say, where you were in the mid-sixties?

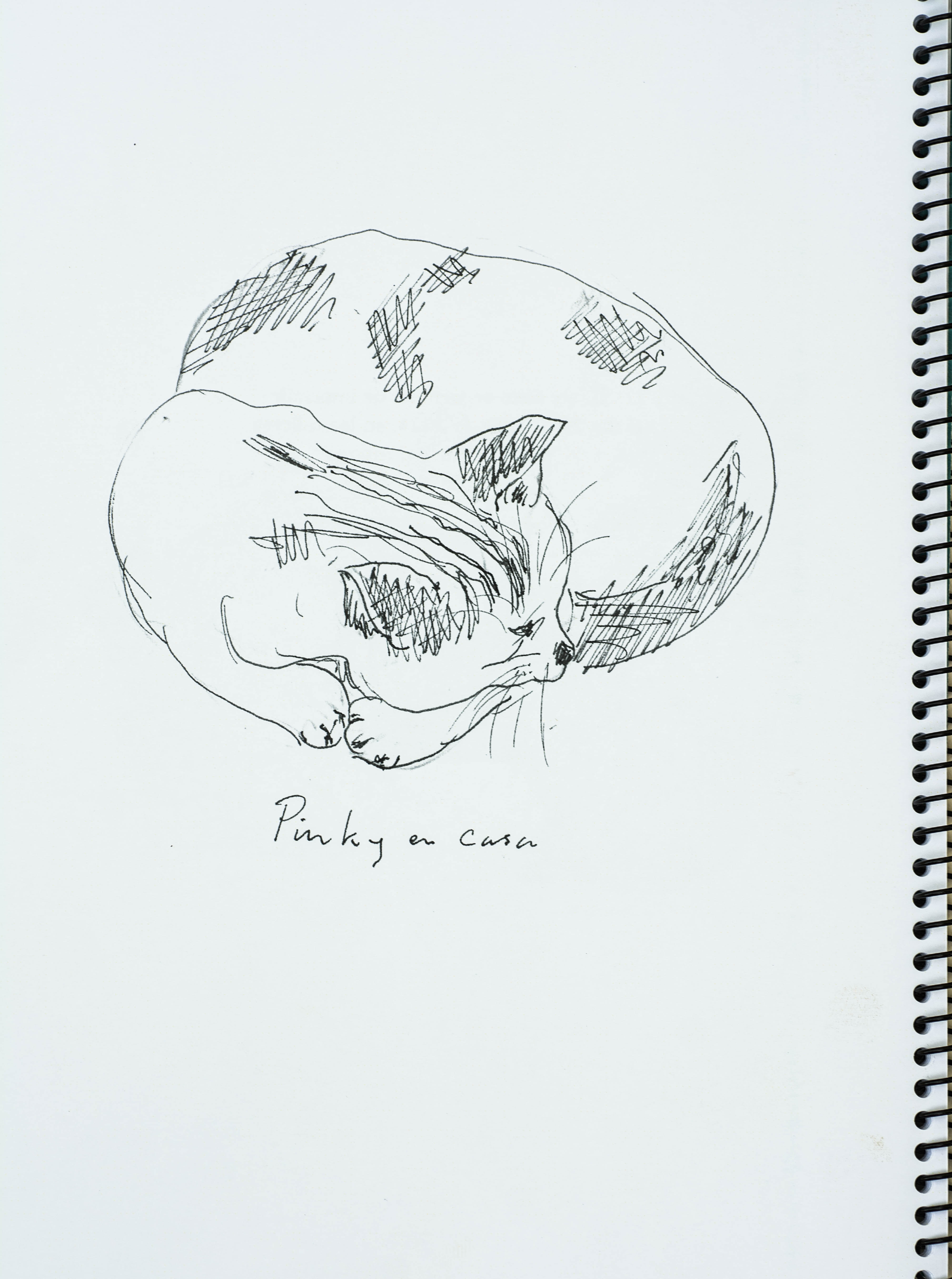

A: I can make some general suggestions, but every artist is a world apart. First and foremost is the importance of actually working, filling sketchbooks, painting, making prints. If you don’t do that conscientiously it’s all pointless. Inevitably, what you are seeking, to live from your art, entails some risk, but it need not be an impediment. There’s a simple formula for taking the stress out of it: Figure out what your wildest dream is and give it a try. The worst that can happen is that you have to go home and get a job.

You’ll have to sell some work, of course. You’ll need to exhibit and participate in art fairs and other cultural events. Whether or not you ever sell much work over Internet, a compelling presence on the Web will be an important element in your success. Your story is just as important as your work and you’ll need to develop it and find interesting ways to divulge it. Right now the media for that are websites and blogs, videos and podcasts and, of course, social media. Later there will be something else but the essential element will still be your story: your humanity, your humor, your best teacher, your hopes, your unexpected successes, the morning light on your nasturtiums, your cat, and your trip to Tasmania or the Grand Canyon. Don’t worry about including any sales pitches. The captivating life and times of a full-time professional artist is sales pitch enough, and your potential clients will appreciate your low-key presentation.

More Preparation

It would be good to study something, too, regardless of whether you get a degree. You will learn how to learn and this will serve you well when it comes time to build a a website or a sailboat. Don’t laugh. A dear artist friend of ours in Colorado makes lovingly- crafted three-quarter size Indian canoes and people hang them from their ceilings.

Travel all you can. Read all you can. Without it you cannot become a complete artist–or person. Read quality fiction and non-fiction. Everything fits into the artist’s blender.

Q: Do you have more suggestions, something to help artists survive a crisis?

A: I discussed that more extensively in an article I wrote some years ago. Here’s a link to it.

Q: What about working space and conditions? How important are they?

A: Ample workspace is essential for a visual artist, especially considering that you might need to mount courses in there. That studio is your sacred space and you must devote some thought and resources to it. You also need privacy and tranquility. At first you may need a day job, but don’t let it prevent you from spending quality time in your studio. Program that into your life. Set some objectives, make some plans. Write them down. They will help you navigate the hard times to come.

Think about what kind of work you’re going to do, how commercial you can go without compromising your creativity and your self respect. Who are you going to sell to and how? Resist the temptation to spend time and effort cultivating rich clients. Normal people–teachers, nurses, programmers, office workers, small business people and the like, are better, more loyal and constant. They will think of you when they need wedding presents or portraits. Then, if a rich client comes along, that’s OK, too.

Don’t despise anyone. My best client for paintings (this was before etchings) when I started out in Granada was a young pharmacy employee. He would phone me occassionally and say, “I’ve got some money saved, Maureen. Can I come out and have a look-around?” We’re still friends.

Q: What about the coronavirus pandemic? How do you think that is going to influence the lives of artists?

A: I think that’s impossible to predict at the moment. The first thing that occurs to me is that involuntary lockdown has given artists valuable time to think and observe, time they have never taken before. I hope they take good advantage of it. As for national and world events, they could go from revolutionary social and political changes to just more of the usual muddling through. Only one thing is clear to me: our creativity–in the broadest sense of the word–will be stretched to its limits Artists may have to plant potatoes. In any case, look on the bright side. Creativity is what artists are good at.

###

Thanks for following, commenting and sharing.

Read Full Post »